The “Basiliad”: The Origins of Christian Charity and Social Ministry

Introduction: The Social Context of the Fourth Century

The fourth century in the history of Christianity was marked not only by intense theological debates but also by the rapid development of institutionalized charity. During this period, private individuals and the Church began establishing the first specialized institutions dedicated to assisting the poor and the needy. Among the most notable initiatives were the hospital founded by Fabiola in Rome, the xenodochium (guesthouse for travelers) established by Pammachius in Ostia, as well as similar institutions in Bethlehem and Sebaste.

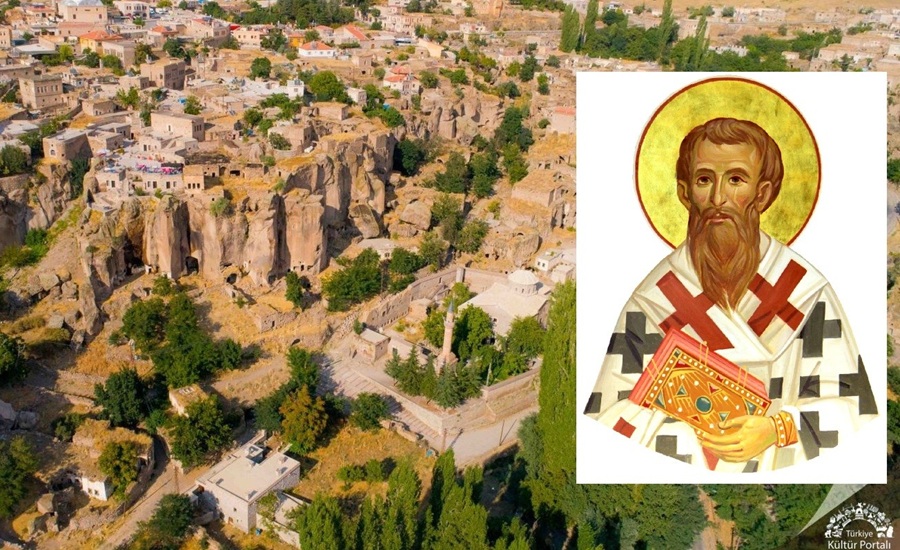

The culmination of these efforts, however, was a project realized in Cappadocia — the Basiliad. This complex functioned almost as a city for the poor and marginalized, founded by BishopBasil the Great (329–379) in response to severe social crises and natural disasters in Anatolia. More than a refuge, the Basiliad became a significant historical landmark that continued to function until the reign of Emperor Justinian (482–565).

The Life of Basil the Great and the Formation of His Vision

Basil of Caesarea, later honored as the Great and recognized as a Doctor of the Church, was born around 329 in Caesarea of Cappadocia (modern-day Kayseri in central Turkey). He came from an eminent family in which holiness was a lived tradition: his grandmother Macrina, his parents Basil and Emmelia, his brothers Gregory of Nyssa and Peter of Sebaste, and his sister Macrina are all venerated as saints.

Basil received an exceptional education, studying in Caesarea, Constantinople, and Athens under the leading rhetoricians and philosophers of his time, including Libanius (314–393) and Himerius (315–386). Following his baptism and extensive travels through Egypt, Palestine, and Syria — where he studied ascetic practices — Basil founded his first monastic community in Pontus. There he formulated monastic rules that became foundational for Eastern monasticism.

Basil insisted that monastic life must unite prayer and Scripture study with manual labor and obedience to a spiritual guide. His conviction that Christian perfection is impossible without service to one’s neighbor later became the theological foundation of the Basiliad.

The Famine of 368–369: A Catalyst for the Project

The immediate impetus for establishing a large-scale charitable center was the devastating drought and famine that struck Caesarea in 368–369. During this crisis, Basil—then still a presbyter — demonstrated remarkable courage and organizational skill. Refusing to abandon the city, he chose instead to share in the suffering of his people and personally coordinate food distribution [1, p. 476].

Employing the full force of his rhetorical gifts, Basil exhorted wealthy citizens to generosity and sharply condemned the “insatiable greed” of merchants who speculated on grain during the disaster. Gregory of Nazianzus (329–390) compared Basil’s actions to the biblical Joseph, who wisely managed Egypt’s resources during famine. Basil established free dining halls, where he himself served the needy, offering not only “simple food” but also the “nourishment of the Word.” This experience demonstrated the need for a permanent institution capable of providing systematic assistance [2, pp. 441–442].

The Foundation and Structure of the Basiliad

Construction of the complex began around 372, shortly after Basil became Bishop of Caesarea. The land for the project was donated by Emperor Valens (328-378) during his visit to the city. The site was located outside the old city of Caesarea, between the first and second milestones from the ancient Greco-Roman center [3, p. 75].

The name Basiliad appears later in the writings of the historian Sozomen (c. 400–450), who described it as “the most renowned refuge for the poor” [4, cols. 1397–1398].

According to Basil’s correspondence — especially his letter to Governor Elias (Letter 94) — the complex was designed as a self-contained settlement with a clearly defined structure:

• Central church: a “great house of prayer” serving as the spiritual heart of the community;

• Residential buildings: housing for clergy arranged around the church, including dignified residences for leadership and more modest quarters for others;

• Xenodochia: guesthouses and shelters for foreigners, pilgrims, and travelers;

• Medical facilities and hospitals: separate buildings for the sick requiring ongoing care;

• Workshops: spaces for crafts and practical labor that enabled self-sufficiency and improved living conditions;

• Transportation infrastructure: including pack animals for transporting supplies and meeting logistical needs [5, cols. 487–488].

Mission: Socially Engaged Monasticism

The Basiliad became the first regularly functioning charitable organization in the Christian world operating under ecclesial authority. Its defining feature was that the staff consisted primarily of monks. Basil radically reinterpreted monasticism, rejecting the purely individualistic asceticism prevalent in Egypt as potentially unproductive. In his view, solitary life contradicted the law of love. Monks were therefore called to realize their virtues through service—caring for the sick, educating orphans, and instructing the young [6, pp. 357–359].

Administration and Relations with the State

Governance of the Basiliad was centralized. Oversight was entrusted to a chorepiscopus, an assistant to the bishop responsible for organizing charitable activities and distributing resources. Basil maintained active correspondence with state officials, defending the rights of the institution and seeking tax exemptions for the monks and hospital.

His arguments were deeply humanitarian: monks, he asserted, had already given their possessions to the poor and their bodies to prayer, leaving them with nothing to tax. Basil believed that political authority derives its legitimacy from God only when it serves the common good, protects widows, and does not turn away from the needy. For this reason, Governor Elias represented for him the ideal ruler — one who actively supported charitable initiatives [6, pp. 361–362].

Transformation into the Core of a Future City

Contemporaries held the Basiliad in high esteem. Gregory of Nazianzus referred to it as a “new city” and a “treasury of piety,” where wealth — freed from moth and thieves — was transformed into aid for the suffering. Gregory of Nyssa (335–394) likened his brother to Moses, who constructed a tangible “tent of meeting” for his people [1, pp. 480-481].

The historical trajectory of the Basiliad proved unique. As the old city of Caesarea gradually declined, centers of life increasingly clustered around Basil’s foundation. In the sixth century, during the reign of Emperor Justinian, new city walls were built around the Basiliad, transforming it into the main urban center. These fortifications later formed the basis of Ottoman defenses. Thus, a Christian charitable complex effectively became the nucleus of the modern Turkish city of Kayseri [2, pp. 458-459].

Conclusion

Saint Basil the Great laid the practical foundations of the Church’s social doctrine. The Basiliad vividly demonstrated that voluntary poverty finds its fullest expression in active love of neighbor. This project transformed monasteries from isolated spiritual enclaves into centers of social assistance integrated into urban life. Basil’s legacy lives on not only in his writings but also in the very fabric of cities — in their architecture and history — shaped upon the enduring foundation of his mercy.

Hieromonk Yeronim Hrim, OSBM

References

1. Mario Girardi. Basilio di Cesarea: le coordinate scritturistiche della “Basiliade” in favore di poveri ed indigenti, in: Classica et Christiana, vol. 9 no. 2, 2014, pp. 459-483.

2. Brian E. Daley, Building a New City: The Cappadocian Fathers and the Rhetoric of Philantropy, in: Journal of Early Christian Studies, vol. 7, no. 3, 1999, pp. 431-461.

3. Susan R. Holman, The Hungry Are Dying: Beggars and Bishops in Roman Cappadocia, New York: Oxford University Press, 2001, 256 p.

4. Sozomen. Ecclesiastical History. Patrologia Graeca, vol. 67, edited by J.-P. Migne, cols. 843-1724.

5. Basil the Great. Letters. Patrologia Graeca, vol. 32, edited by J.-P. Migne, cols. 219-1112. The letter to Governor Elias responds to defamatory accusations brought against Basil — particularly by Arian bishops — following the initiation of the large-scale charitable complex.

6. Stefania Scicolone, Basilio e la sua organizzazione dell’attività assistenziale a Cesarea, in: Civiltà Classica e Cristiana, vol. 3, no. 1, 1982, pp. 253-372.

Basilian Order of Saint Josaphat

Basilian Order of Saint Josaphat