St. Basil Becomes His Own Thinker

“We who have been entrusted with the ministry of the Word should always be zealous for the perfecting of your souls.”[1]

Introduction

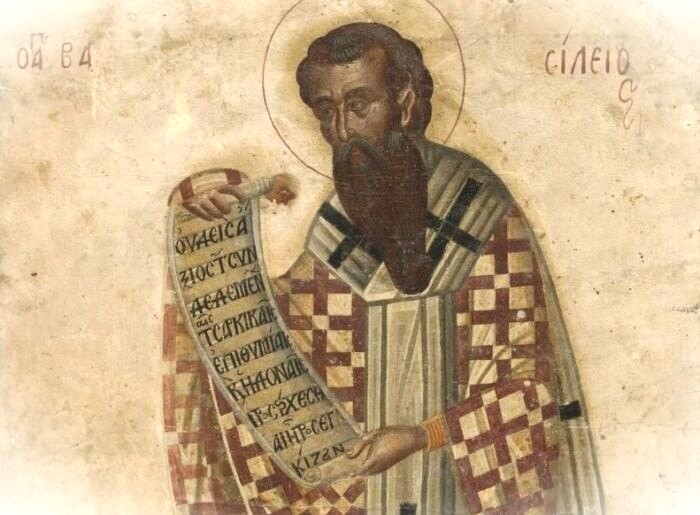

St. Basil of Caesarea (†379) occupies a foundational place in the development of Christian asceticism and Trinitarian theology. While his dependence on earlier figures such as Eustathius of Sebaste, Gregory of Nazianzus, and his sister Macrina has long been acknowledged, modern scholarship increasingly recognizes that Basil’s lasting importance lies not in simple transmission but in creative reform and synthesis.[2]

This study argues that Basil gradually emerges as his own thinker, shaping a distinct ascetic theology that integrates evangelical radicalism with ecclesial responsibility. His development from disciple to authoritative spiritual master parallels his ecclesial trajectory from ascetic leader to bishop. Basil’s originality consists not in founding monasticism ex nihilo, but in reforming an existing movement, disciplining ascetic enthusiasm, and embedding the ascetic life firmly within the life and mission of the Church.

1. Early Formation and Intellectual Independence

Basil’s ascetic formation occurred within a dense network of relationships and movements. The influence of Eustathius of Sebaste was particularly significant, introducing Basil to a rigorous form of asceticism closely allied with Homoiousian theology.[3] Macrina, meanwhile, embodied a lived synthesis of renunciation, prayer, and communal discipline, while Gregory of Nazianzus provided intellectual companionship and moral support.[4]

Yet Basil’s relationship to these figures was never one of passive dependence. Even in his earliest letters, Basil demonstrates independence of judgment and a concern for discernment. His refusal to permanently join Macrina’s community, as well as his insistence on developing his own ascetic vision at Annisa, already suggests a thinker testing inherited models rather than simply reproducing them.[5]

Crucially, Basil begins writing about ascetic life from the very start of his commitment. This early literary activity indicates a transition from personal experimentation to intentional teaching, a trajectory that will culminate in the Asceticon.

2. Basil as Ascetic Leader and Teacher

Ancient sources testify to Basil’s leadership among ascetics even before his ordination. Rufinus famously compares Basil and Gregory of Nazianzus to the two olive trees of Zechariah 4, though his account exaggerates Gregory’s dominance.[6] Basil’s own correspondence suggests the opposite: he persuades Gregory to return to the ascetic ideal and directs the location and form of their shared experiment.[7]

More importantly, Basil’s leadership takes concrete form in written instruction. References to horoi and kanones in early letters indicate that Basil was already formulating norms for ascetic life.[8] Whether these refer to the Moralia or to epistolary instruction, the evidence points to Basil’s early role as a teacher whose authority rested on spiritual discernment rather than institutional office.

The consistency between Basil’s early ascetic writings and the later Asceticon demonstrates a coherent and developing vision. Basil does not present himself as a local superior, but as one responding pastorally to ascetics across a wider network, many of whom likely belonged to the broader Eustathian movement.[9]

3. Priesthood, Ecclesial Conflict, and the Expansion of Basil’s Vision

Basil’s ordination and involvement in ecclesiastical affairs profoundly shaped his ascetic teaching. His ascetic life and clerical commitment developed in tandem, each forcing a reinterpretation of the other.[10] The theological conflicts of the 350s and 360s — particularly the rise of Homoean and Anomoean positions — brought Basil into direct engagement with the wider Church.

Basil’s participation in synods, his association with leading Homoiousians, and his eventual theological maturation all contributed to a widening of his ascetic horizon. Asceticism could no longer remain an inward-looking pursuit; it had to serve the unity and truth of the Church.

During this period, Basil’s answers to ascetical questions likely began to circulate more widely, forming the nucleus of what later became known as the Small Asceticon.[11] His role among ascetics increasingly paralleled his growing prominence in ecclesial circles, particularly as the exile of Eustathius created a vacuum of leadership.[12]

4. The Asceticon as a Mature Synthesis

The Asceticon represents the mature expression of Basil’s ascetic thought. Structured as responses to concrete questions, it reflects lived experience rather than speculative abstraction. Basil consistently resists individualism, insisting that ascetic life be communal, obedient, and oriented toward love of neighbor.

Unlike more enthusiastic movements, Basil rejects uninterrupted prayer detached from work, the abandonment of social responsibility, or disdain for ecclesial structures.[13] Ascetic practice is always measured against the commandments of Christ and the building up of the community.

This approach transforms asceticism from a charismatic movement into a durable ecclesial tradition. Basil’s authority lies not in severity but in balance, and his teaching displays remarkable pastoral realism.

5. Charity and the Basileiados

Basil’s synthesis of asceticism and charity finds its most visible expression in the Basileiados, the complex of institutions for the poor, sick, and marginalized outside Caesarea.[14] Far from being peripheral, this project embodies Basil’s conviction that ascetic renunciation finds its fulfillment in service.

Gregory of Nazianzus famously describes the Basileiados as a “new city,” placing it immediately after his account of Basil’s monastic activity.[15] Basil himself explicitly associates care for the poor with ascetic teaching, viewing such service as an essential expression of obedience to Christ.[16]

By integrating ascetic discipline with social responsibility, Basil decisively reshapes the Christian understanding of holiness. This synthesis would profoundly influence later Eastern Christian spirituality.

6. Enthusiasm, Heresy, and Discernment

The fourth century witnessed intense ascetic ferment, including groups later labeled Manichaean, Encratite, or Messalian. Basil’s correspondence reveals his engagement with such movements, neither dismissing them outright nor endorsing their excesses.[17]

His responses in the Asceticon consistently discourage extremes, insisting that authentic zeal (spoudē) must be tested by obedience, work, and ecclesial communion. Where “pre-Messalian” ideas appear in ascetic questions, Basil’s answers are invariably corrective.[18]

This discerning posture places Basil between institutional rigidity and charismatic anarchy, enabling him to integrate ascetic enthusiasm into the life of the Church without allowing it to become schismatic.

7. The Break with Eustathius and Basil’s Theological Maturity

The eventual rupture between Basil and Eustathius marks a decisive stage in Basil’s development. While ascetic disagreements contributed, the fundamental cause was theological — specifically Eustathius’ ambiguous position regarding the divinity of the Holy Spirit.[19]

Basil’s refusal to compromise on Trinitarian doctrine, even at the cost of friendship, reveals the primacy of ecclesial truth in his thought. His On the Holy Spirit stands as a monument to this conviction.[20]

Following this break, Basil’s ascetic teaching gains increasing authority, while Eustathius and his followers fade into marginality. As Basil’s theology is eventually recognized as orthodox by the Council of Constantinople (381), so too his ascetic synthesis becomes normative in Asia Minor.[21]

Conclusion

St. Basil becomes his own thinker not by rejecting tradition, but by reforming and integrating it. His ascetic doctrine evolves through lived experience, theological struggle, and pastoral responsibility. By uniting ascetic radicalism with ecclesial obedience, charity, and doctrinal clarity, Basil offers a vision of Christian life that is both demanding and enduring.

His achievement lies in transforming asceticism from a potentially schismatic movement into a stable ecclesial vocation. In doing so, Basil secures his place not merely as a historical figure, but as a perennial teacher of the Church.

Hieromonk Gabriel Haber, OSBM

Bibliography

Primary Sources

• Basil of Caesarea. Ascetical Works. PG 31.

• Basil of Caesarea. Letters.

• Basil of Caesarea. On the Holy Spirit.

• Gregory of Nazianzus. Orations and Letters.

• Gregory of Nyssa. Against Eunomius.

• Rufinus. Historia Ecclesiastica.

• Socrates. Historia Ecclesiastica.

• Sozomen. Historia Ecclesiastica.

Secondary Sources

• Elm, Susanna. Virgins of God: The Making of Asceticism in Late Antiquity. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994.

• Gribomont, Jean. Histoire du texte des Ascétiques de saint Basile. Louvain, 1953.

• Rousseau, Philip. Basil of Caesarea. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

• Stewart, Columba. Working the Earth of the Heart. Oxford, 1991.

• Brown, Peter. The Body and Society. New York: Columbia University Press, 1988.

[1] Basil of Caesarea, Preface to the Shorter Rules.

[2] J. Rousseau, Basil of Caesarea (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 84-85.

[3] E. Elm, Virgins of God (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994), 46-66.

[4] Gregory of Nazianzus, Oration 43.

[5] Basil, Letters 1-2.

[6] Rufinus, Historia Ecclesiastica 11.9.

[7] Gregory of Nazianzus, Letters 14, 19.

[8] Basil, Preface de Fide (CPG 2886).

[9] Basil, Letter 223.

[10] Rousseau, Basil of Caesarea, 84-85.

[11] H. Gribomont, Histoire du texte des Ascétiques de saint Basile (Louvain, 1953), 152-156.

[12] Socrates, Historia Ecclesiastica 4.26.

[13] Basil, Shorter Rules 238.

[14] Basil, Letter 150.

[15] Gregory of Nazianzus, Oration 43.63.

[16] Basil, Letter 31.

[17] Basil, Canonical Letters 188, 199.

[18] Elm, Virgins of God, 188-195.

[19] Basil, Letter 223.

[20] Basil, On the Holy Spirit.

[21] Sozomen, Historia Ecclesiastica 6.15-17.

Basilian Order of Saint Josaphat

Basilian Order of Saint Josaphat